The Orthodox Study Bible, Ancient Faith Edition, Hardcover: Ancient Christianity Speaks to Today’s World

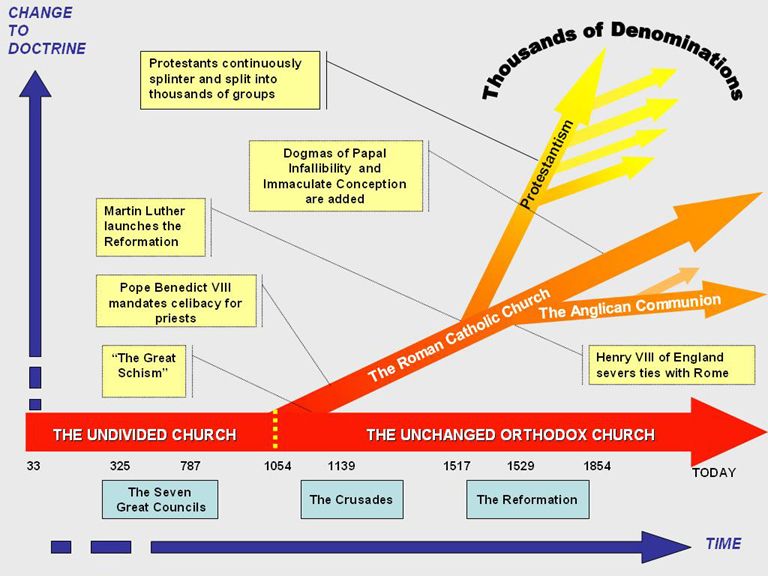

THE GREAT SCHISM

Conflict between the Roman Pope and the East mounted—especially in the Pope’s dealings with the bishop, or patriarch, of Constantinople. The Pope even went so far as to claim the authority to decide who should be the bishop of Constantinople, in marked violation of historical precedent. No longer operating within the government of the New Testament Church, the Pope appeared to be seeking by political means to bring the whole Church under his domination.

Bizarre intrigues followed, one upon the other, as a series of Roman popes pursued this unswerving goal of attempting to control all Christendom. Perhaps the most incredible incident of these political, religious, and even military schemes occurred in the year 1054. A Cardinal, sent by the Pope, slapped a document on the altar of the Church of Holy Wisdom in Constantinople during the Sunday worship, excommunicating the Patriarch of Constantinople from the Church!

The Pope, of course, had no legitimate right to do this. But the repercussions were staggering. Some dismal chapters of Church history were written during the next decades. The ultimate consequence of the Pope’s action was that the whole Roman Catholic Church ended up dividing itself from the New Testament faith of Orthodox Christianity. The schismhas never been healed.

As the centuries passed conflict continued. Attempts at union failed and the Roman Church drifted farther and farther from its historic roots. There are inevitable consequences in deviating from the Church. The breaking away of Rome from the historic Orthodox Church would prove no exception.

FURTHER DIVISIONS IN THE WEST

During the centuries after AD 1054, the growing distinction between East and West was becoming indelibly marked in history. The East maintained the full stream of New Testament faith, worship, and practice—all the while enduring great persecution. The Western or Roman Church, crippled because of its schism from the Orthodox Church, bogged down in many complex problems. Then, less than five centuries after Rome committed itself to its unilateral alteration of doctrine and practice, another upheaval was festering—this time not next door to the East, but inside the Western gates themselves.

Though many in the West had spoken out against Roman domination and practice in earlier years, now a little-known German monk named Martin Luther inadvertently launched an attack against certain Roman Catholic practices which ended up affecting world history. His famous Ninety-Five Theses were nailed to the Church door at Wittenburg in 1517. In a short time those theses were signalling the start of what came to be called in the West the Protestant Reformation. Luther sought an audience with the Pope but was denied, and in 1521 he was excommunicated from the Roman Church. He had intended no break with Rome. Its papal system of government, heavy with authority, refused conciliation. The door to future unity in the West slammed shut with a resounding crash.

The protests of Luther were not unnoticed. The reforms he sought in Germany were soon accompanied by demands of Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich, John Calvin in Geneva, and hundreds of others all over Western Europe. Fueled by complex political, social, and economic factors, in addition to religious problems, the Reformation spread like a raging fire into virtually every nook and cranny of the Roman Church. The ecclesiastical monopoly to which it had grown accustomed was greatly diminished, and massive division replaced its artificial unity. The ripple effect of that division impacts even our own day as the Protestant movement itself continues to split and shatter.

If trouble on the continent were not trouble enough, the Church of England was in the process of going its own way as well. Henry VIII, amidst his marital problems, replaced the Pope of Rome with himself as head of the Church of England. For only a few short years would the Pope ever again have ascendency in England. And the English Church itself would soon experience great division.

As decade followed decade in the West, the many branches of Protestantism took various forms. There were even divisions that insisted they were neither Protestant nor Roman Catholic. All seemed to share a mutual dislike for the Bishop of Rome and the practice of his Church, and most wanted far less centralized forms of leadership. While some, such as the Lutherans and Anglicans, held on to certain forms of liturgy and sacrament, others, such as the Reformed Churches and the even more radical Anabaptists and their descendants, questioned and rejected many biblical ideas of hierarchy, sacrament, historic tradition, and other elements of Christian practice, no matter when and where they appeared in history, thinking they were freeing themselves of Roman Catholicism. To this day, many sincere, modern, professing Christians will reject even the biblical data which speaks of historic Christian practice, simply because they think such historic practices are “Roman Catholic.” To use the old adage, they threw the baby out with the bathwater without even being aware of it.

Thus, while retaining, in varying degrees, portions of foundational Christianity, neither Protestantism nor Catholicism can lay historic claim to being the true New Testament Church. In dividing from the Orthodox Christianity, Rome forfeited its place in the Church of the New Testament. In the divisions of the Reformation, the Protestants—as well-meaning as they might have been—failed to return to the New Testament Church.

Source: The Orthodox Study Bible, Ancient Faith Edition, Hardcover: Ancient Christianity Speaks to Today’s World

Timeline Of Church History | A Consistent and Unbroken Tradition: Timeline Of Church History | The Roman Catholic Church added to Orthodoxy and the Protestants subtracted from Orthodoxy.